Kéré: The new Archetype of the Socially-conscious Architect

by Shruthi Ramesh, Learner – Batch 9, Writing/s in Architecture

The Social Responsibility of the Architect

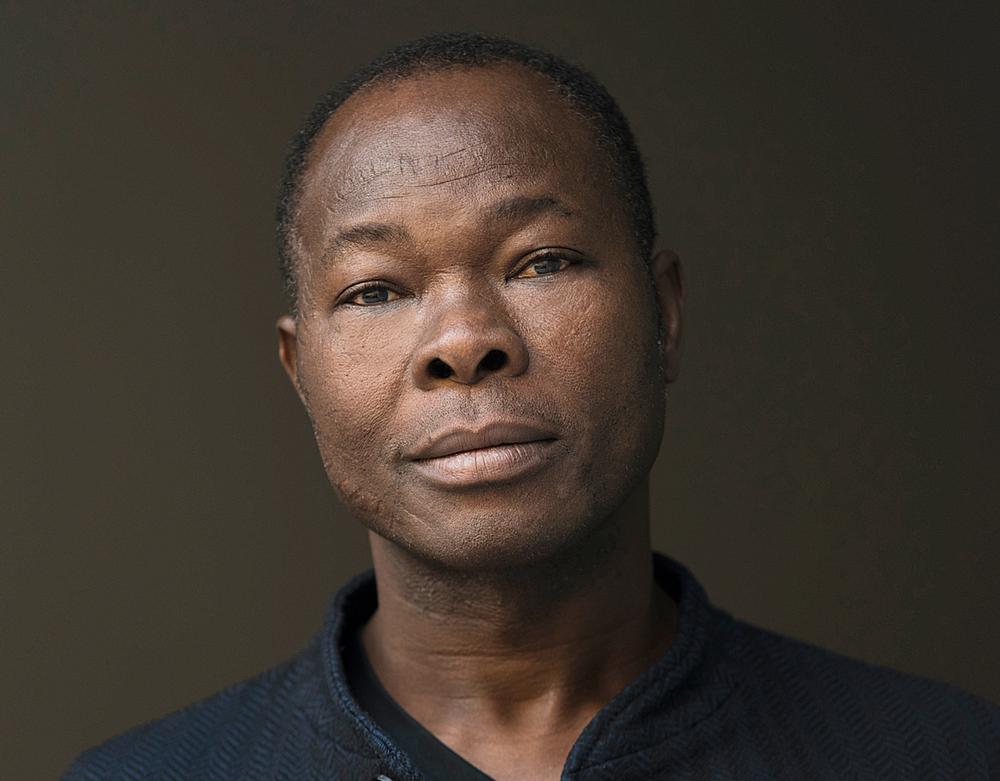

This writeup expands on the theme of the social responsibility of the architect by doing a profile on the 2022 Pritzker Laureate and celebrated social architect, Diébédo Francis Kéré whose practice emanates social commitment and innovation. By profiling Kéré, the intent is to understand the theme social responsibility of the architect from the realistic and grounded experiences of the architect themselves.

The awarding of the Pritzker Architecture Prize 2022 to architect Diébédo Francis Kéré symbolised the evolution of the socially conscious archetype of the architect into the new gold standard in architecture. Right from its inception in 1979, but specifically in the first decade of the 21st century, the Pritzker Prize has celebrated iconography in architecture, whether in the works of Zaha Hadid, Peter Zumthor, Jean Nouvel, or Richard Rogers. It was only in 2016 that an architect who interwove social responsibility with economic demands and forged wholesome solutions for human habitation, the Chilean architect Alejandro Aravena, became a Pritzker Prize laureate. Since then, the collective consciousness in architecture has been reoriented, to value architects who deploy social sensibilities. In this regard, Kéré has become a game-changer and his recognition as a Pritzker Laureate represents a pivotal shift in the lasting perception of what good architecture is.

Diébédo Francis Kéré was born in 1965 in Burkina Faso, a land-locked country in West Africa, and received an advanced degree in architecture from the Technical University of Berlin, Germany. He founded his architectural practice, Kéré architecture in 2005 in Berlin and oscillates his professional and personal commitments between Germany and Burkina Faso, as a dual-citizenship holder of both countries. His parent’s emphasis on his education obligated him to endure the big city alone, away from his family from the very young age of seven, in order to access education, as his village did not have schools at the time. Later, he was fortunate enough to receive scholarships to Germany, first to undergo a vocational carpentry program and later to study architecture. Being the first person in Gando to receive a University degree motivated him to reinvest in Africa through education and architecture.

Kéré has managed to meaningfully connect the community through his architecture. His most notable work and the very first building he built, the Gando Primary School, completed in 2001, with an extension in 2008, uses architecture to fulfill a multitude of social responsibilities. Built as a part of his graduating project, in his birth village Gando in Burkina Faso, the primary school which won the Aga Khan Award for architecture in the 2002-04 cycle, was designed to combat extreme heat and poor lighting conditions prevalent in schools in his country. It is noteworthy that he was still a student at his university when he raised the 50,000 USD through crowdfunding for the construction of the school. The buildings, made of indigenous clay were not just built for the community, but also built by and with them.

In a TED Talk from 2013, the visionary architect iterated the motivation behind his move to give back to his community, ‘the privilege of education’ he received, by building the primary school where there was none. He uses architecture to nurture sustainable ecosystems, foster education as a tool for building equity, and improve health and sanitation. Not many architects can boast of reforesting large parcels of land or building to give back to the community in the way Kéré has done. In the context of extreme scarcity – Burkina Faso is one of the poorest countries in Africa with limited natural resources, the architect designs environments that uplift and create equitable futures.

While recognizing Kéré as an African architect of merit, the Pritzker jury however accorded his European education as setting the table for his superior architectural sensibilities. Sans the privilege of his European education and practice based out of Berlin, would he have met the prevalent Euro-centric criteria for good architecture? Would he have still come to be recognized globally for his contribution to architecture? At the end of the day, this speaks volumes of the necessity to decolonize the architectural profession and global architectural consciousness and is in no way an affront to the brilliance of Kéré as a rooted socially conscious architect. While explaining his architectural philosophy, he remarks, “everyone deserves quality, everyone deserves luxury, and everyone deserves comfort. We are interlinked and concerns in climate, democracy and scarcity are concerns for us all”, reiterating his unparallel sense of duty towards the people and his desire for social equity through conscious design.

In his architecture, one can perceive a strange syncretism of the primordial with the futuristic. A new and evolved style of context sensitivity is crystallised, dissimilar from the Critical Regionalism of the past. His take on context taps into local culture, tradition, and material but remain astutely contemporary in architectural expression. He adds an edge by using innovation to supplement traditional techniques, for example, the expansive suspended roofs over his buildings as a mechanism for thermal comfort and passive cooling, and the use of cut clay pots to infuse natural light in the Gando Library. His mastery in merging cultural symbolisms is evidenced in the design of the colourful Sarbalé Ke (House of Celebration) pavilion for the Coachella festival in California in 2019. The pavilion remains quintessentially Coachella in language and expression, coloured in hues picked from Indio’s sunsets, while deeply rooted in Burkinabé culture through its embodiment of the Baobab tree in its twelve towers. His playful indulgence with natural light, ventilation, and shade across projects speak of an individual hyper-aware of the intricacies of the built environment he sets out to craft. With a distinct and ever-evolving architectural language across educational, healthcare, and public architecture in African countries and temporary installations in developed nations, such as the Serpentine Pavillion (the UK, 2017), his architecture is different from his contemporaries in being everything other than a shiny glass building.

There is something earthy about the architecture of Kéré, which connects humans to the built environment, through a conscious emphasis on rooted materiality, all the while carrying forward an “afro-futurist vision”. Beyond using local materials, the futuristics and contemporality distinguish Kéré’s designs from those of other socially-conscious architects of renown such as Hassan Fathy. Rather than alienating his community by imposing western ideas of building and construction that he would obviously have learned during his time in Germany, he chose to involve the masses by indulging them in the existing Burkinabé tradition of collective building, fortified by community participation. By doing so, he was able to give his community a sense of purpose, and desire to create and teach them valuable skillsets of building construction through which they could transform their livelihood and improve social standing. By creating better opportunities for their education through his architecture, he invested in the future generations of his community. Kéré magnificently redefines social architecture as soulful, inspiring, and innovative, through his significant contributions to the built environment.

Bibliography:

- https://www.pritzkerprize.com/laureates/diebedo-francis-kere

- https://www.kerearchitecture.com/

- https://www.kerefoundation.com/en

- https://www.archdaily.com/979080/architecture-is-much-more-than-art-and-it-is-by-far-more-than-just-buildings-in-conversation-with-francis-kere

- TED Talk. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MD23gIlr52Y&t=156s

- https://www.pritzkerprize.com/laureates/ale-jan-dro-ara-ve-na

- https://youtu.be/vQtgbnH6OG8

- https://www.dezeen.com/2022/03/15/diebedo-francis-kere-projects-roundup-architecture/

- https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/mar/15/it-is-unbelievable-francis-kere-becomes-first-black-architect-to-win-the-pritzker-prize

Shruthi Ramesh is an Architect and Urban Designer based out of Kerala. Her penchant for reading is matched by an equal predilection for writing.

A 6-week long journey of discovering the art and craft of writing in architecture, Batch 9 of the online course held by award-winning architectural journalist, author, curator, and editor – Ar. Apurva Bose Dutta concluded on August 20th, 2022.

Registrations for Batch 10 are now open. To celebrate 10 batches and 2 years of this course, we have a special offer on the fee! Click here to join the course and ace the art of putting pen to paper.