Walking, Healing

By Ar. Prayash Giria

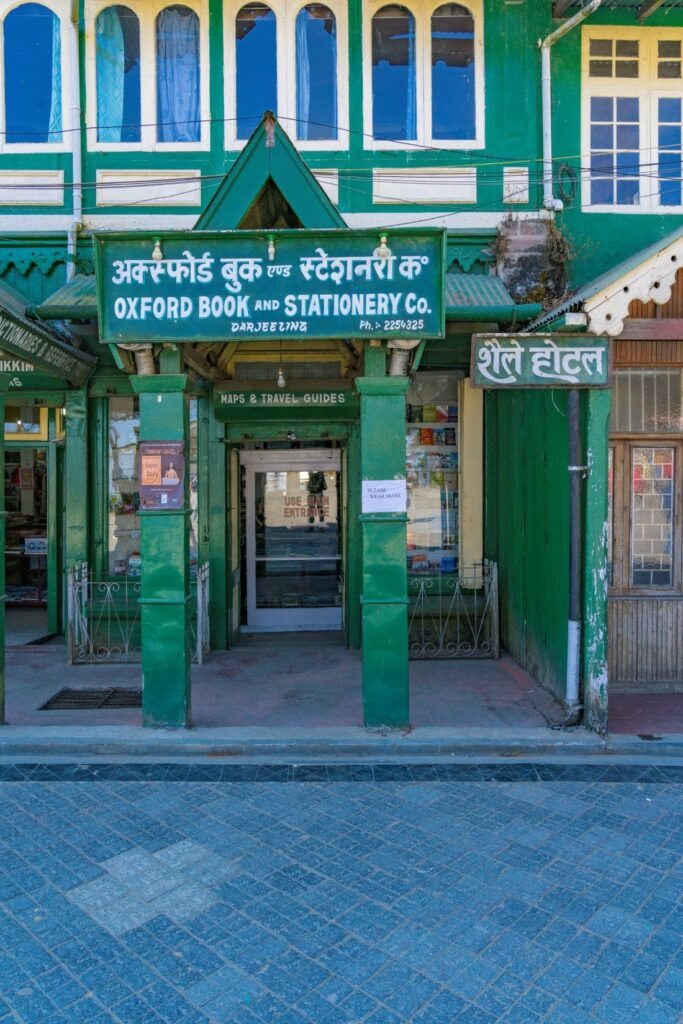

Last winter, I celebrated the end of a successful trek to Sandakphu with a few days of self-pampering in Darjeeling. While there, I walked into the venerable Oxford Bookstore and ended up purchasing a copy of ‘The Snow Leopard’ by Peter Matthiessen. I had only vaguely heard about the book before and had presumed it to be a deft travelogue describing Matthiessen’s arduous trek through western Nepal. Being a self-identified ‘mountains guy’, I snapped it up immediately.

Upon reading, however, I found out that it was a much more meditative piece of writing, frequently digressing from descriptions of mountainous landscapes, flora, and fauna, to memories of his late wife, Deborah, and musings on life and loss. The book ended up striking a much deeper chord with me than I’d expected – like Matthiessen, I too had grief on my mind, having lost my wife, Shoma, to a brain tumour two years prior. To read that the seemingly mundane act of walking in the mountains could bring such healing and acceptance to Matthiessen was heartening and inspiring.

Thus, in a curious case of ‘after’- shadowing, ‘The Snow Leopard’ prompted me to revisit my own trek with a more introspective lens. I improvised by running through my photos – I am not a writer nor a prolific journal-keeper like Matthiessen – and what began to emerge was a parable for moving through and with grief.

The trek began at Manebhanjan, a ramshackle border town a few hours west of Darjeeling. It’s a curious, confusing place, hanging somewhere between village and town, ridge and valley, road and forest, home and abroad. It was a bit like the beginning of grief itself, a strange and confounding place where everything feels familiar but also wholly different.

From Manebhanjan, the trail climbs ever upward on a spindly road with countless hairpin bends, inducing much frustration and fatigue. It was on what I think was the 22nd bend that my guide, James, chuckled and asked me to stop counting. ‘Just focus on getting to the next turn’, he told me wisely. Remembering his words, I felt they applied equally well for processing loss as well – just focus on getting through life one day at a time.

The trail eventually opened out above the clouds, at the village of Meghma, where we spent our first night on the trail. Here, I came across three commemorative chortens, built by locals in memory of their ancestors. Placed atop a hill to be figuratively closer to the heavens, the chortens also kept a watchful gaze over the village below. This made me think about the nature of memory and remembrance. Those in grief are often advised to ‘move on’, but the chortens serve to show that memory can be catalytic as well, encouraging those left behind to continue living.

I revisited the chortens next morning and had from there my first view of Kanchenjunga. The world’s third-highest mountain, the star attraction of this trek, peeked ever so slightly from behind the much lesser hill in front of me. I could still see the trail zigzagging menacingly in the foreground, but the hint of Kanchenjunga beyond reinvigorated me. It was a bit like chancing on a happy memory while trying to work through loss – it acts as a counterweight to all the pain, and pushes you to work your way through it all.

From Meghma, a long and punishing hike switchbacks across a valley of the Singalila National Park by way of steep stone staircases and rough forest paths. Every step magnified the pain in my knees, the weight on my back, the labour in my breath, and the sweat in my brow. It made me feel viscerally alive. In retrospect, I think this section of the trek served to remind me of myself, to tell me that I was more than just my loss.

The same section of the trek is also prone to wafting mist, and you often find yourself enveloped in thick clouds, only to re-emerge in the bright sun seconds after. It’s much the same in grief – no one moves through it linearly, in a clean-cut, ever-progressing line. You move back and forth through hope and sadness, gaining a little perspective each time.

As if to reinforce my earlier point, I emerged out of the mist just in time to watch the sun set into a sea of clouds, below my feet. It was an incredible sight that brought back many happy memories of Shoma.

The next morning began from the shores of Kalipokhari, a sacred lake wedged into a windswept saddle. Its banks are lined with prayer flags, tied, I imagine, by locals and trekkers hoping to pass on messages to loved ones they can no longer talk to.

The path from Kalipokhari trudges on ever upward, through terrain that gets progressively sparser. As you reach the summit of Sandakphu, you begin to realize that you’ve grown accustomed to the solidity of the walk, to the lightness of the air, to the brightness of the mountain sun. It’s a bit like living with grief – slowly but surely, you learn to live alongside it, even appreciate it for how it’s shaped you so.

Once you reach the summit of Sandakphu, you’re rewarded with grandstand views of Kanchenjunga, the world’s third-highest peak, spreading at what seems like arm’s length. You stare in awe for a while, before realizing that you’ve made it this far already and that it was the mountain that spurred you every step along the way. It reminded me of how far I’d come from that wintry night of 2018 when I cried my heart out outside the ICU, and how the memory of Shoma helped me get through life one moment at a time. Kanchenjunga, thus, became a figurehead for both, the constancy of grief, and its beautiful ability to inspire.

The next morning, before beginning my descent from Sandakphu, I took in the sunrise and caught distant views of Everest, Lhotse, and Makalu, the world’s first, fourth, and fifth tallest mountains respectively. I imagine that these mountains are figureheads for someone else’s grief as well, much like Kanchenjunga was for mine. The thought reminded me that grief and loss are universal, and the idea that there are many others who could understand my loss and empathize with my sorrow felt reassuring.

Dipping below the clouds and the treeline, the trail feels the same but also different. It’s still steep and knee-jarring, but its also easier and swifter to navigate. It’s not too different with grief – with time and effort, navigating it also starts feeling easier and more natural.

As the trail begins to sink under your skin, you begin to take note of the small details on the wayside – in my case, blink and miss wildflowers. The ‘new normal’ begins to take hold, much like life after loss.

The next few days of the trek run along a network of mountain streams. At Gurdum Khola, I marked the second anniversary of Shoma’s passing. It was a quiet, hauntingly beautiful spot, the sound of the gushing water and birdsong reminding me of Shoma practicing her ragas. I remember thinking that there wasn’t a better way to remember her.

As the trek draws to a close, you return to signs of life. At hamlets like Timburay and Srikhola, you bask in quietude even as larger villages and towns glimmer on slopes at the far end of the valley. Reinforced and reinvigorated by the trek, you feel ready to take on the big city again. Loss too steels you the same way for sundry life, lending newer perspectives to work with.

Seven days and 75 kilometres later, you find yourself in Darjeeling and its myriad creature comforts. As distracting as they can be, nothing quiet matches up to the majestic profile of Kachenjunga looming over town. I feel this is a bit like my life – or the life of anyone who lives alongside grief. They bustle of life catches up again and takes them in, but the shadow and dignity of their loss stays solemnly in the background.

The trek, in retrospect, reached its figurative end – and beginning – at Oxford Bookstore, where I picked up my copy of ‘The Snow Leopard’ from. The title alludes to the elusive mountain cat, which Matthiessen had hoped to see when he started his trek. He never did see the snow leopard but did not regret it either, as being on the trail allowed him to understand and appreciate the loss and absence better. “These hard rocks instruct my bones in what my brain could never grasp in the Heart Sutra, that ‘form is emptiness and emptiness is form’—the Void, the emptiness of blue-black space, contained in everything”, he writes, and I feel I can understand exactly what he said.

Prayash Giria is a Delhi-based urban development planner moonlighting as a travel photographer. An alumnus of SPA Delhi and UCL, he works with WRI India to support policymaking toward sustainable urbanization.